Mondragon is the world’s largest worker co-operative group with around 75,000 workers in ~100 co-operatives and an annual turnover of €12bn. I was lucky enough to visit them last month as part of the “Co-operators of the 21st Century” programme organised by Association of Friends of Arizmendiarrieta.

There’s lots of information about Mondragon which I won’t attempt to reproduce here – their corporate video, Wikipedia page, annual report and interview with Democracy Now are good places to start.

This blog is about the things that surprised and inspired me about Mondragon, with particular reference to our own (currently) more modest co-operative network – CoTech – which is having its second national meetup in November.

Lesson 5: Co-operatives are businesses first

Worker co-ops in the UK quite often have a political/social/ideological element that is largely lacking from the Mondragon co-operatives. It might be more accurate to say that Mondragon’s ideology is largely contained within worker co-operativism – they believe in good jobs, fair pay and democracy – as opposed to a broader political movement. This can be a weakness as well as a strength but I believe it has been key to Mondragon’s success as it’s given them a strong focus for investment as opposed to UK co-ops that tend to spread themselves very thinly around supporting political, environmental and other social movements. I feel we could do a better job of helping those movements if we got to a turnover of €12bn first.

Lesson 4: Mondragon have it much harder than we do

Mondragon focus on heavy industry which requires a lot of investment to create jobs. According to my guide, retired director Mikel Lezamiz, in many of the Mondragon co-ops it takes an investment of ~ €500,000 to create one new job. Compare that to the cost of creating a new job in CoTech – around £500 for a laptop. To help with this, each Mondragon member invests about €15,000 to help capitalise the businesses.

Mondragon also had a tough time at the outset – they were started in a deep recession, in an underdeveloped part of the county, under a fascist government, during the second world war with little or no capital. Mondragon provides entry level jobs in highly-competitive markets such as food retail. Despite not being ideologically driven Mondragon have a very low pay differential (the CEO is paid six times more than the lowest paid worker). This differential is twice as high as Outlandish (where the ratio is 3:1) but because they offer entry level jobs it means the CEO of the 75,000-person network is paid slightly less than the highest paid person at Outlandish who helps manage the ~20 people that work here. I found that a bit embarrassing, but more inspirational.

Lesson 3: Use structure judiciously and ensure that the members (owners) are the people or organisations for whom the co-op is vital

UK co-ops seem to love a bit of complexity – multi-stakeholder co-ops, consortium co-ops, the ‘Somerset rules’, secondary co-ops, platform co-ops, etc. Partly this is because UK law makes co-ops complicated, partly it’s because people like innovating with the model and partly (I think) it’s because models hold the appeal of a ‘big idea’ that might be a unicorn and solve everyone’s problems without too much hard work. Mondragon has a great structure – a secondary co-op (e.g. purely owned by member co-ops) which all Mondragon co-ops jointly own (notice that they own it, it does not own them); pretty much all the co-ops are pure worker co-ops with the exception of a few consumer/worker multi-stakeholder co-ops (including their supermarket) and a few consultancy co-ops that sell services to the other Mondragon co-ops.

In this last category, Mondragon make use of a multi-stakeholder co-op model in which the co-ops (usually not all the co-ops) and the employees share ownership. For example, Atagi offers collective purchasing services to Mondragon co-ops – it buys gas, steel, oil, consultancy, etc. – cheaper than it would be on the open market and resells these products and services to its members. Not all the Mondragon co-ops are members (owners/investors) of Atagi as it’s not relevant to all of them. It sells services to the non-member co-ops to companies outside the Mondragon group, but not as cheaply as it sells them to its member co-ops. I’m hoping that we can borrow this model for CoTech.

Lesson 2: We’ve got a long way to go

Mondragon have their own bank, their own social security system, a co-op incubator that makes our own Space4 and even the Co-op Group’s Federation look embarrassingly naive, a dedicated co-operation training centre set in their 14th century palace and their own university. Lots of the CoTech co-ops are not sure how they’ll raise the ~£350 for a cost-price ticket to the CoTech AGM. We have a long way to go, but it’s going to be an exciting journey.

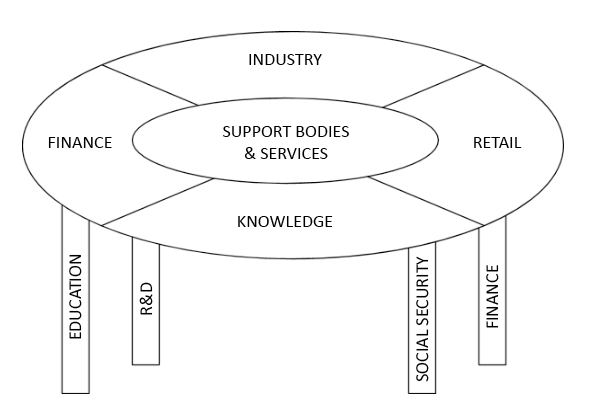

Mondragon describe their structure as being like a table. The ~100 co-operatives make up the surface of the table, divided into four sectors plus a number of secondary/support co-ops. The four ‘legs’ of the table – education, research and development, social security and finance – are things that need to be provided outside the co-ops, while other vital functions such as marketing, sales and ensuring equality are embedded in each co-operative. CoTech still has to work out which piece of furniture we’re modelled on, but we probably need some legs.

Lesson 1: We are not alone, and we should co-operate

One of the main purposes of the event was to bring together co-operators from different networks with similar aims. Firstly, there are many Mondragon co-ops we can learn from including Lanki (who specialise in pedagogy), Fagor Arrasate (who build heavy machinery for the world’s leading manufacturers) and Mondragon University (who teach co-operativism and pedagogy alongside engineering, business studies and gastronomy). Secondly, there are other networks of early stage co-operatives including OlatuKoop, TEKSFabrika, Tazebaez, Co–opolis and Mondragon in Europe, as well as our sister movements such as TechWorker in the US and Enspiral in New Zealand.

Look familiar? OlatuKoop is not so different from CoTech or Outlandish.

Look familiar? OlatuKoop is not so different from CoTech or Outlandish.

Graduates of Mondragon’s LEINN entrepreneurship programme run Tazebaez – Basque slang for ‘why not?’ – a ‘junior co-op’ that might one day become part of Mondragon.

The workplace at Fagor Arrasate – a Mondragon co-op that builds production lines – would be unfamiliar to most CoTech members, but the ideas behind the way they work sounds very familiar.

The CoTech crew are ready to take their place as good global co-op citizens.