As many fellow project managers working on complex, greenfield or innovative projects know, there’s always an inherent tension between big, fuzzy ideas at the start and technical feasibility. At best, this tension can be grounding – but more often than not, it’s a tricky one to resolve.

Falling in Love with the Big Idea…

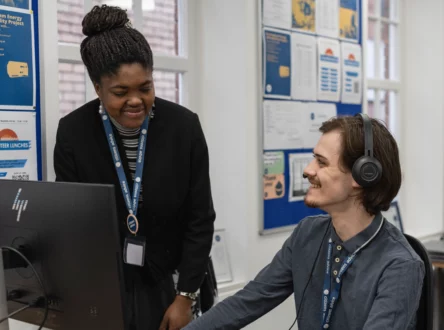

Have you ever tried running a design sprint at the start of a project? We are big fans of collaborative design sprints. We invite our partners, often the final users of the product, to get involved and share their thoughts and lived experiences.

We aim to create a safe and welcoming space to unearth the deepest needs, even those that users themselves may not yet be fully aware of. These needs often emerge naturally during a design sprint.

The problem with big ideas, though, is that they can sound a bit intimidating to development teams (and others). Imagine trying to immediately translate every speculative idea you hear into development scope – all while trying to figure out how it fits into the existing setup and what’s technically possible at all.

That’s why we believe that translating the outputs of a design sprint into a realistic yet ambitious prototype is a crucial process. It’s not the bit you want to rush through or cut corners on.

Falling in Love with the Problem

Perhaps instead of falling in love with the big idea, we should be falling in love with the problem we’re trying to solve for our users.

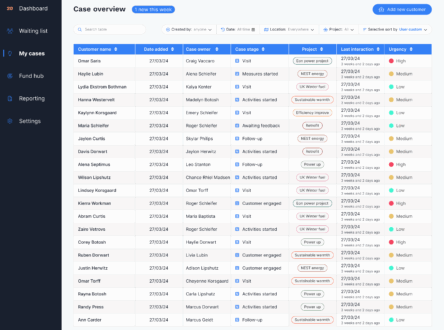

In our case, gathering requirements for advanced reporting functionality in NookCRM was challenging.

We knew there were numerous templates available, but we weren’t sure how representative they were. There’s little to no standardisation in the community energy sector, as different funders require different KPIs, which complicates life for organisations, especially smaller groups that lack the time and resources for extensive reporting.

Our number one goal is to make something that simplifies this. We aim to deliver a simple UX for a complex, multi-layered system, such as enabling users to create their own reports while slicing, aggregating, and manipulating data in their CRM. The biggest compliment we get from our partners using Nook is how user-friendly it is — easy to pick up, even for those with lower levels of digital literacy. We’re determined to keep it that way!

Translating the Prototype into Decisions

Our tech lead, Ben, commented that the reporting concepts introduced in the wireframes by our designer, Kieran, were excellent and aligned perfectly with the overall vision for the reporting functionality we shaped together during the design sprint. I couldn’t agree more – especially the overarching structure centred on “reporting blocks”. That concept became a foundation for many later decisions.

However, challenges began to emerge once we started translating wireframes into actual functionality. Reporting is heavily data-based, and since developers have the deepest understanding of the data structures, they naturally started asking questions that hadn’t been considered by Kieran, who produced the wireframes.

Take the case selection process, for example. We had to figure that out during the build sprint. We were creating reusable reports where configuration isn’t a one-off task — you need filters, like “cases in a certain demographic” or “cases for a specific project”. When re-running a report, you’re suddenly dealing with two layers of case selection.

When Ben and I looked back on the sprints and discussed ways to streamline the design sprint process and get quicker answers to these thorny questions, an idea emerged: why not build a low-fidelity functional prototype together? A version that’s rough around the edges but allows the team to explore how things actually connect — for example, how reports should relate to projects (funding sources). Doing this early, collaboratively, could save a lot of time later and reduce the number of follow-ups once a designer returns to the project.

We also realised that it’s not always obvious whether a roadblock is a “developer question” or a “designer question” — especially in tools like Nook, where both UX workflows and underlying data structures play a big role.

It’s All About Iterations

In agile product development — which we at Outlandish use across all our projects — iteration is king.

One thing we’d like to do in future projects is intentionally build in time and space for developer-designer iterations. Designers are often stretched thin across multiple projects, so it’s tempting to just book them for a solid block of time to produce a high-fidelity prototype. What’s harder is scheduling regular check-ins during the build sprint — but that’s where so much value lies.

Without that ongoing contact, developers may have to make decisions on key functionality without a designer’s input. That can slow things down and sometimes leads to features that haven’t been fully thought through in the broader user experience context. It’s usually much quicker — and more cost-effective for the project — for a designer to sketch a possible solution and give everyone something concrete to chat through and make decisions.

Regular check-ins help designers stay informed about ongoing decisions and evolving priorities, allowing them to contribute to solutions before blockers appear. They also fit naturally within an agile approach: short, frequent touchpoints keep the whole team aligned, reduce the need for rework, and ensure design and development move forward together in small increments.

Design sprints are just the beginning

To wrap up, the end of a design sprint isn’t the end of designer–developer collaboration — far from it. It’s really just the starting point for a partnership that continues to evolve through short, focused iterations during the build sprints. And if the budget allows, giving the whole team space to create a low-fidelity functional prototype together before leaping into high-fidelity design can make a world of difference.

Once you step out of the design sprint room — walls plastered with post-its, sketches, and scribbles — the ideas shouldn’t freeze in place. They should keep growing, taking shape as practical decisions that balance technical feasibility with big ideas, all rooted in the real problems we’re trying to solve for our users.